And you thought the debate over entitlements is rough today… Over the next decade we will be having, what I’m sure will be an incredibly contentious, national conversation about basic income.

1. Preying on the Promise of Higher Education

There’s a promise we make to the next generation: Graduate from college and you can get ahead. Indeed, recent studies show that college graduates earn $1 million more than high school graduates over their lifetimes.

Yet, as we make this promise, public higher education institutions nationwide are facing a troubling trend of disinvestment. Even with poorly treated adjuncts and other nontenure-track contingent faculty doing the lion’s share of teaching at many colleges, tuition costs keep rising. Even with current federal and state student loans and grants, students have been saddled with crippling debt.

And then there’s another side of higher education. For-profit colleges are defined by putting profit before the public good, earnings over education, shareholders above students. At these schools — such as Corinthian Colleges Inc., which filed for bankruptcy this month, and ITT Tech, which is being investigated by the Securities and Exchange Commission for alleged fraud — students are products, faculty are afraid to tell accreditors the truth about where they work, and taxpayers foot the bill for aggressive marketing that preys on first-generation college students, veterans and students of color.

Funded largely by taxpayers, for-profit colleges get close to 90 percent of their funding from federal aid — that’s more than $30 billion annually. The industry feeds off our noble national goal to ensure higher education is a ladder of opportunity for all who want to climb. However, instead of offering an affordable path to a better tomorrow, they leave students with an uncertain future. Seventy-two percent of these for-profit schools produce graduates who earn less, on average, than high school dropouts.

Currently, for-profit schools enroll just 9 percent of all postsecondary students but account for nearly half of all student loan defaults. They allocate about 23 percent of their revenue to recruiting and marketing and just 17 percent to academic instruction. Compare that with institutions where academics are the priority, such as community colleges, which spend 80 percent or more on instruction.

2. Truck Driver as Endangered Species

Late last year, I took a road trip with my partner from our home in New Orleans, Louisiana to Orlando, Florida and as we drove by town after town, we got to talking about the potential effects self-driving vehicle technology would have not only on truckers themselves, but on all the local economies dependent on trucker salaries. Once one starts wondering about this kind of one-two punch to America’s gut, one sees the prospects aren’t pretty.

We are facing the decimation of entire small town economies, a disruption the likes of which we haven’t seen since the construction of the interstate highway system itself bypassed entire towns. If you think this may be a bit of hyperbole… let me back up a bit and start with this:

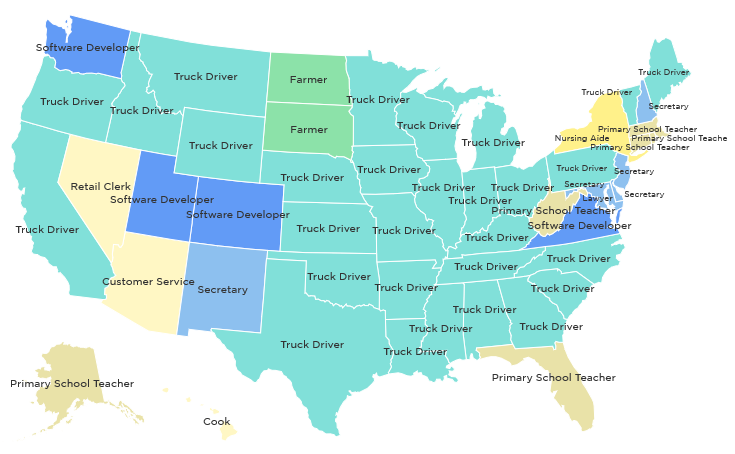

Source: NPRThis is a map of the most common job in each US state in 2014.

It should be clear at a glance just how dependent the American economy is on truck drivers. According to the American Trucker Association, there are 3.5 million professional truck drivers in the US, and an additional 5.2 million people employed within the truck-driving industry who don’t drive the trucks. That’s 8.7 million trucking-related jobs.

We can’t stop there though, because the incomes received by these 8.2 million people create the jobs of others. Those 3.5 million truck drivers driving all over the country stop regularly to eat, drink, rest, and sleep. Entire businesses have been built around serving their wants and needs. Think restaurants and motels as just two examples. So now we’re talking about millions more whose employment depends on the employment of truck drivers. But we still can’t even stop there.

Those working in these restaurants and motels along truck-driving routes are also consumers within their own local economies. Think about what a server spends her paycheck and tips on in her own community, and what a motel maid spends from her earnings into the same community. That spending creates other paychecks in turn. So now we’re not only talking about millions more who depend on those who depend on truck drivers, but we’re also talking about entire small town communities full of people who depend on all of the above in more rural areas. With any amount of reduced consumer spending, these local economies will shrink.

3. Rise of the Machines: A primer on Artificial Intelligence

In a speech in October at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Mr Musk described artificial intelligence (AI) as “summoning the demonâ€, and the creation of a rival to human intelligence as probably the biggest threat facing the world. He is not alone. Nick Bostrom, a philosopher at the University of Oxford who helped develop the notion of “existential risksâ€â€”those that threaten humanity in general—counts advanced artificial intelligence as one such, alongside giant asteroid strikes and all-out nuclear war. Lord Rees, who used to run the Royal Society, Britain’s foremost scientific body, has since founded the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, in Cambridge, which takes the risks posed by AI just as seriously.

Computers can now do some narrowly defined tasks which only human brains could manage in the past (the original “computersâ€, after all, were humans, usually women, employed to do the sort of tricky arithmetic that the digital sort find trivially easy). An image classifier may be spookily accurate, but it has no goals, no motivations, and is no more conscious of its own existence than is a spreadsheet or a climate model. Nor, if you were trying to recreate a brain’s workings, would you necessarily start by doing the things AI does at the moment in the way that it now does them. AI uses a lot of brute force to get intelligent-seeming responses from systems that, though bigger and more powerful now than before, are no more like minds than they ever were. It does not seek to build systems that resemble biological minds. As Edsger Dijkstra, another pioneer of AI, once remarked, asking whether a computer can think is a bit like asking “whether submarines can swimâ€.

The worry that AI could do to white-collar jobs what steam power did to blue-collar ones during the Industrial Revolution is therefore worth taking seriously. Examples, such as Narrative Science’s digital financial journalist and Kensho’s quant, abound. Kensho’s system is designed to interpret natural-language search queries such as, “What happens to car firms’ share prices if oil drops by $5 a barrel?†It will then scour financial reports, company filings, historical market data and the like, and return replies, also in natural language, in seconds. The firm plans to offer the software to big banks and sophisticated traders. Yseop, a French firm, uses its natural-language software to interpret queries, chug through data looking for answers, and then write them up in English, Spanish, French or German at 3,000 pages a second. Firms such as L’Oréal and VetOnline.com already use it for customer support on their websites.

Technology, though, gives as well as taking away. Automated, cheap translation is surely useful. Having an untiring, lightning-fast computer checking medical images would be as well. Perhaps the best way to think about AI is to see it as simply the latest in a long line of cognitive enhancements that humans have invented to augment the abilities of their brains. It is a high-tech relative of technologies like paper, which provides a portable, reliable memory, or the abacus, which aids mental arithmetic. Just as the printing press put scribes out of business, high-quality AI will cost jobs. But it will enhance the abilities of those whose jobs it does not replace, giving everyone access to mental skills possessed at present by only a few. These days, anyone with a smartphone has the equivalent of a city-full of old-style human “computers†in his pocket, all of them working for nothing more than the cost of charging the battery. In the future, they might have translators or diagnosticians at their beck and call as well.

4. Windfarms as Nocebos

Nice writeup on how expectations guide perceptions of technology.

Any new technology carries the unexpected in with it, like a bright pin on the jacket. Health researchers picked at what might be happening between the blades, the noise, the infrasound, the electromagnetic fields. What They Found May Surprise You. Plot out the complaints onto a map, and you’ll see that they don’t actually line up against where windfarms are, nor of the size of the turbines themselves. Trawl back through the peer-reviewed literature on ‘wind turbine annoyance‘ and again, see no causal relationship between people living in proximity to wind turbines, emitted noise, and physiological health effects.

What there are instead, by the barrel, are expectations. The majority of complaints in Australia took place well after the farms had been up and running for several years, but shortly after anti-wind farm groups became vocal about health concerns. Visions and sounds do not exist in a vacuum, but are given meaning by the very personal context in which they arise – what you see and what you hear depends on what you expect.

You retire. You sell your house in the city; you buy a larger one in the countryside, in England’s green and pleasant land. Rolling fields, local pubs, long shadows on cricket greens, (you are perhaps John Major). Blackbirds warbling in the trees. Peace. Quiet. And then there on the horizon, on the hill past the new home, is a bloody great wind turbine. Cold white metal, looming like a bastard over your lovely landscape. You see it when you wake in the night and open your curtains. You see it in the morning when you come downstairs and look outside. You hear it. (You think you hear it).

Windfarms are thus nocebos – inert substances that cause harmful effects arising from whatever expectations are loaded onto them and what effects they are perceived to cause. Those who complained of the windfarms were those who had heard frightening information about how the turbines would harm their health; those who don’t like wind farms; and those who simply, from their window, from the door, could see them.

“Our dilemma is that we hate change and love it at the same time; what we really want is for things to remain the same but get better.” -Sydney J. Harris

If you were forwarded this newsletter and enjoyed it, please subscribe here:Â https://tinyletter.com/peopleinpassing

I hope that you’ll read these articles if they catch your eye and that you’ll learn as much as I did. Please email me questions, feedback or raise issues for discussion. Better yet, if you know of something on a related topic, or of interest, please pass it along. And as always, if one of these links comes to mean something to you, recommend it to someone else.